[Hi–This is something I (K) wrote up for my students in my Fashion and Digital Media class last semester. Some of it is based on the work we’ve done starting Aux Etoiles.]

As I’ve mentioned, I recently began research into the Etsy shop, vintage clothing seller world. I’ve been conducting a participant observation (or ethnographic) study of this culture since last March. I’ve opened an Etsy shop with one of my BFFs to more fully participate in this world and its work. This culture covers a vast amount of geographical, cultural, and digital space and, while I don’t have hard numbers yet, it’s mostly populated with women. Briefly, women (and some men) set up shops on platforms such as Etsy, Instagram, or blogs where they sell vintage clothing. Each step of this process involves numerous forms of labor, which I’m slowing mapping out. For instance, setting up a shop on Etsy requires the following steps: finding stock, cleaning/mending/ironing it (that vintage smell is real, and stubborn); styling the garments; photographing the clothing; measuring; writing up descriptions; tagging the listings with SEO terms; pricing; and posting on the Etsy app.

These categories can be broken down even further. For example, finding stock requires regularly visiting thrift stores and going through the racks piece by piece. Finding estate sales, connecting with people who are clearing out stock, or hitting up the clothing recyclers who have enormous bins of discarded clothing they sell by weight/bundle (and this is an area I need to investigate). Many, (and again no numbers yet, or ever…this is qualitative!) Etsy shop owners also have Instagram accounts set up to promote their shop and tap into wider audiences. There’s work in Instagramming as well, which I will definitely get to at a later time.

There are various routes and places to find old stuff but most involve understanding what has value in todays market. Part of the reason I got into this was the rise of the “prairie” dress. Growing up in Kansas, Nebraska and Texas, the whole prairie style thing was familiar. I knew I could get my hands on it with a few trips to local thrift stores. And this is what finding stock entails, sifting through stores such as Goodwill, various church store thrifts, Savers, Sals, etc. One of the things that’s mind blowing is just how saturated these places are with discarded fast fashion items (forever 21, etc). These items have little to no value on the vintage market. Finding older stuff, stuff pre 1995, is the goal. Military items are always great too, especially if older. There is a thrill in finding a wool sheath dress from the 1960s or a velvet dress coat from the 1940s.

This brings me to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU)–finding a tag with this logo is a sign the item is pre 1995, which is when the union dissolved. Garments with this label were made in America, in the Northeast, South, and West. Many of the chapters of this union were mixed racial and ethnic workers. Some brutal battles were fought through this union.

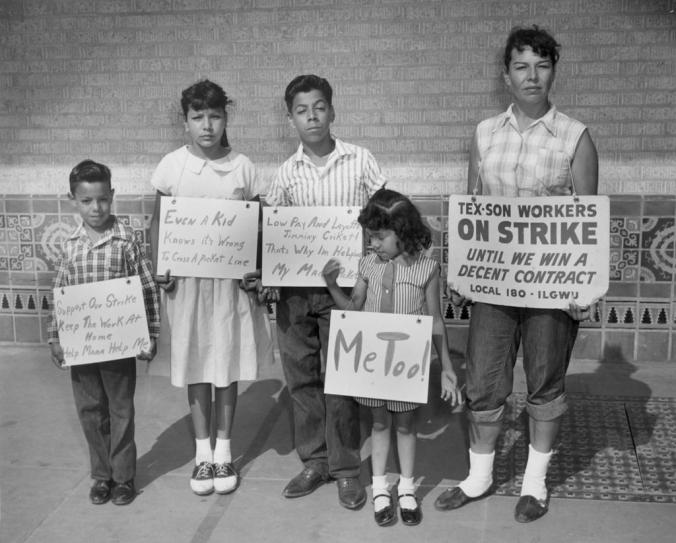

What I’ve learned so far about the history of the ILGWU is fascinating. The union came to be because young immigrant women were working in terrible conditions, getting sexually harassed, and dying. Two large strikes caught the attention of the world, and especially the rich elite women of NYC who stood with the garment workers. The early garment workers were men. Women were brought into the factories as independent contractors to make shirtwaists. Prior to working in the factory, women garment workers worked out of their homes. Bringing them to the factory exposed them to harassment but it also allowed them to organize together. Women were kept out of the unions initially because they were not seen as skilled laborers (there’s a connection here to, well, so many other spheres of labor: women’s labor is routinely considered unskilled). Also fascinating is that the union presidents were always men. Here’s an image from the Tex-Son Strike. The women deliberately played up their maternalism and used children to counter the narrative that they were violent. Most of the workers were Mexican. The stereotype of Mexicans as violent has a LONG history, as do all stereotypes. The use of children in the strike also showcased how their wages supported families. From the images I’ve seen so far, the police physically brutalized numerous women on the strike.

Part of the thrill of vintage digging is imagining who had the item previously, and the conditions and worlds surrounding it. Finding an item with the union tag signals that it was made in America and part of a larger economy of manufacture, labor, laws, and trade. I can’t help but wonder about the women working in the union, making garments, that are found and re-sold by the millions of women working through digital platforms today. The union workers organized to have fair wages, a limited number of hours per week, numerous benefits, such as educational opportunities, and a pension. The digital and creative workers today have none of these things. And while digital/creative workers are not considered unskilled, necessarily, their work is not taken seriously. It’s seen as a “choice” or a hobby, and definitely feminine pursuit. As we’ve discussed all semester, whenever women do something, it’s devalued. Part of what I aim to uncover are the economics behind the creative labor of vintage sellers.

I also want to take up the ways fashion both separates and, sometimes, unites classes of women. In the case of the early garment workers, when the wealthy caught wind they used their influence to help out. Similarly, we see how businesses can really tank if the world catches wind of their deplorable labor conditions. Garment work has always been feminized work. The mass production of garments ushered in the Industrial Revolution in the West and continues to modernize economies in developing countries. The digital revolution is similarly built on the massive amounts of ‘work’ done by women, even if that’s taking selfies and sharing on Instagram. Women not receiving anywhere close to the lion share of wealth created in and through both technological revolutions is the thread that binds these different moments in time.

Stumbled on your excellent blog doing research on ILGWU. Love everything in my closet with that proud label!

LikeLike